This post is a continuation of Maps and Mapmakers Behind Them. Part I and Part 2 and is an adaptation of the talk I gave at the Catalyst Club in Brighton in August. This time I write about pirate maps, dungeon maps and the second most tattood man in the world.

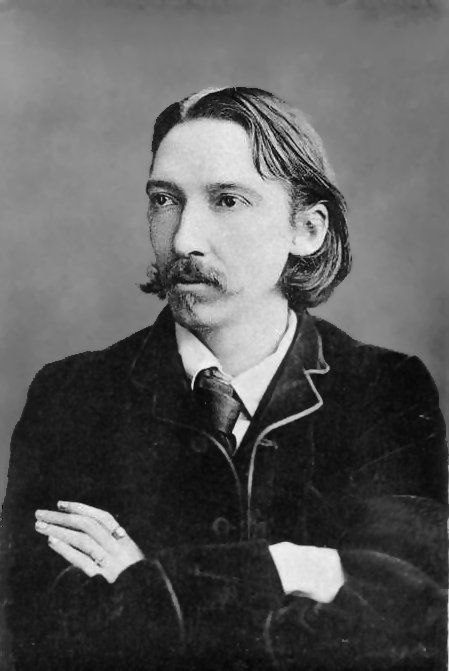

We’ll jump forward to the end of the 19th century. Now it’s 1881 and this is Robert Louis Stevenson, Scottish author of ‘Treasure Island’, a story first serialised in the children’s magazine ‘Young Folks’. Literacy is becoming more widespread, the children’s act is in it’s infancy (young children should be in school) and there is more leisure time for some strata of society. There is time for making maps for fun.

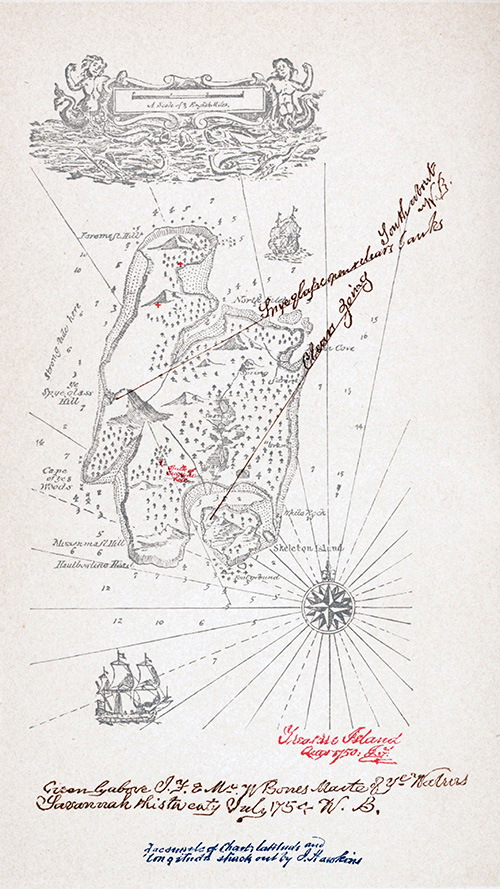

And this is the map Robert Louis Stevenson created for ‘Treasure Island’. It’s a great example of a map used purely for entertainment and as fictional illustration, not for documentation, knowledge sharing, bonding purposes, status or survival. And it could be said that this map is the first ever pirate treasure map, influencing almost all books about pirates onwards. Although it’s a familiar literary subject, there are very few documented cases of pirates actually burying treasure in reality, and no documented cases of historical pirate treasure maps. Very probably it’s also the first to use the idea of ‘x marks the spot’, something that we take for granted on all pirate maps now. How incredible is that? An entire understanding of a subject in Western Culture changed due to a simple map.

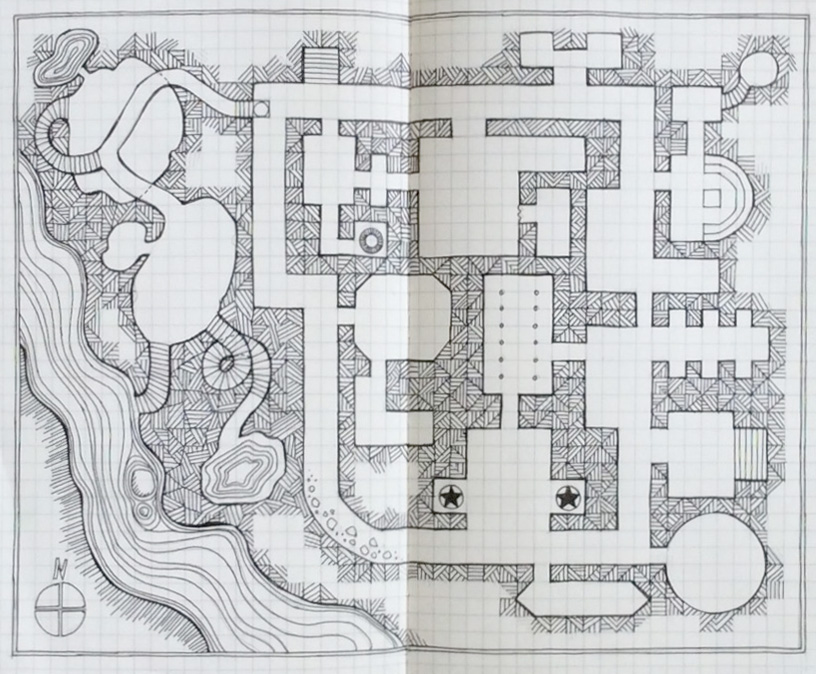

Our next map story is this one. This is a hand drawn map used specifically for the tabletop fantasy role-playing game, Dungeons and Dragons. Traditionally played by geeky teenagers in geeky teenage bedrooms, the game has been around for over 40 years and is still incredibly popular- despite several court cases in the 1980s by the US religious right who argued that D&D encouraged Satanism and suggested it was ‘a feeding program for occultism’.

The Dungeon map is integral to the game, used by the Dungeon Master who oversees all, often creating the map and the story itself. He describes the location and dilemma to the players and they, as a party, make decisions about their next move. Actions are decided on by the role of a dice.

Originally these kind of maps were drawn out by hand on gridded paper with standard symbols generally accepted by the D&D community. The Dungeon Master needed to think about how he could provide the most exciting dungeon space to give ‘good game’ for the players. So there should be a variety of features (crypts, tunnels, secret entrances), definitely several exits and entrances (so no-one gets cornered) and also a variety of levels. What interests me about these maps is that they are so personal but made specifically for the enjoyment of other people. It’s the game that is important.

The map above is based on those by award winning mapmaker, Dyson Logos, and the style with cross hatching, thick black lines and lovely use of empty space has many followers. In an interview Dyson stated that his favourite character to play was an ”axe-mage’ who basically runs around half naked with a black leather hood over his head.’

It wasn’t possible to find any decent photos of Mr Logos online…

And at this point we have entered a true internet tunnel of darkness because it is at this point my access to copyright free images has run dry. So… I will have to use my powers of description and you will have to imagine or otherwise distract your reading pleasure by heading to the links that I have usefully provided to see any images for this last section.

It is 1977 and you are looking at map of Baltimore . It shows a gridded road system viewed from above, densely packed with intricately drawn tower blocks seemingly rising from the page in dark reds and greys and olive greens.

It’s an axonometric map, an easy way to draw a map that looks as if it is 3D. It doesn’t use true perspective. There is no horizon line, things in the distance look the same size as those in the foreground (so no foreshortening) and there is no vanishing point. Axonometry is sometimes called parallel perspective because most angles are the same – the lines in each direction are parallel to each other.

The map was commissioned by Baltimore City Planning Department as a promotional tourist poster. What’s interesting is that the muted colours and almost conservative fastidiousness of this maps belies the mapmaker’s true character.

The mapmaker’s name is Jim Hall. He’s an older man of medium build and greying hair. All fairly mundane until you get closer and see that he’s covered in tattoos from head to toe, from ear to ear. Every single inch of skin, even his face, is blue and etched in darker blue comma-like patterns.

On retiring from town planning, a small obsession with tattooing started. And then continued. And continued. Until Jim became the second most tattooed man in the world and renamed himself the Blue Comma. He’s even got tattoos on his eyeballs.

Additionally he also decided on some body modifications and I quote, ‘What started out as a penis extension turned into three extra testicles…’

Yes, three.

Perhaps in this case, the personality of the mapmaker wasn’t able to come out through his mapmaking and it was a lifetime of concentrating on such detail that led to a need to break out in some way. Or perhaps it’s the opposite and the map truly reflects an interest in obsessive detail and patterning, leading to another life of obsessively patterning the landscape of the body instead.

Whatever, in summing up, I hope you can see that there have been many different ways and personal reasons to map in the past, be that to document, to share knowledge, to have power, protect, play or survive. Maps are coloured by the society they are made in. Hand drawn and made maps are always curated and edited personally by the mapmaker though and through craftsmanship or draughtsmanship, individual personalities can shine through.

As knowledge is shared, and technology improves, mapping becomes perhaps more homogeneic and despite our culture’s deep attachment to expressing ourselves as unique individuals with our own personal narratives, I wonder whether the days of maps with individual character and story are gone.