This post is a continuation of Maps and Mapmakers Behind Them. Part I and is an adaptation of the talk I gave at the Catalyst Club in Brighton in August. I became interested in how hand made mapping techniques differ and in particular, how the personality of the mapmaker can be seen in each work – something increasingly lost in 21st century digital maps.

This next mapmaker is a map making celebrity and one of my favourite cartographers ever. His name is John Ogilby and he lived in 17th century Great Britain. His story is so full of highs and lows, it wouldn’t look wrong on an ‘X Factor’ contestant’s cv.

He was born into a desperately poor Scottish family, and tragically, his father was thrown into a debtor’s prison forcing young John to be the main breadwinner of his family. But he worked hard, earning enough to buy a lottery ticket. Incredibly, he won and used the winnings to pay back his father’s debts and release him from prison. The remainder he used to train as a dancing instructor.

His career started to grow and he became well known, teaching the children of wealthy land owners and growing rich. Tragically, it was not to last. An unfortunate accident caused by some high spirited leaping at a masked ball, made sure he was never to dance again and he was lamed for life.

His disability didn’t stop him though. Further adventures followed including setting up the first national theatre in Ireland, becoming involved in the civil war, escaping an explosion in a castle and surviving a shipwreck. Incredibly, he managed to return to England where, having learnt Latin and Greek and become a translator, he decided to build his own printing press, eventually specialising in printing atlases. Eventually we get to the maps…

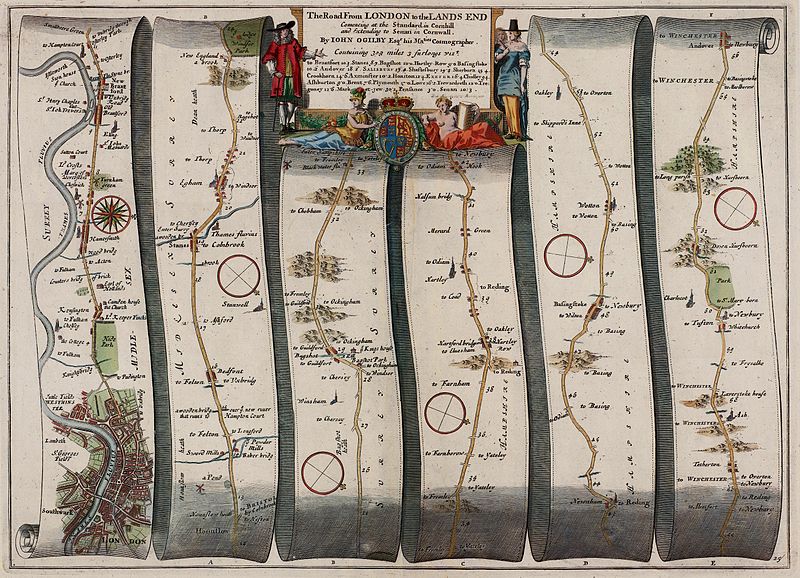

This is one of John Ogilby’s works. This format is called a ‘strip map’ which usually depict a particular route from one place to another and show the features encountered on the way (like settlements or rivers) in a striplike format. Sometimes the strips are placed next to each other like this and the map is read starting at the left from top to bottom and then back to the top again. The non essential details – the mountains you might see in the distance on your travels – aren’t documented at all. I love Ogilby’s maps for the highly personal annotations and the characterful cartouches (the illustrated title panels) he adds.

Britain at the time is becoming more populated and towns more established. There is a rough road system but communications often take weeks. It’s the early days of the postal service – postboys race across the countryside on horseback- so maps are becoming increasingly important. The highpoint of John Ogilby’s career is the publication of his Britannia Atlas, which was one of the most accurate and detailed road maps of its time and became the standard form for road maps for years later.

Intriguingly there is some speculation whether one of the purposes of the atlas was as an invasion map to facilitate a Catholic takeover. It’s a huge piece of work, very comprehensive and commissioned by Charles II. He had pro – Catholic sympathies, making deals with France at the time and given John Ogilby’s theatrical life, I really wouldn’t be surprised if there was another agenda going on behind it.

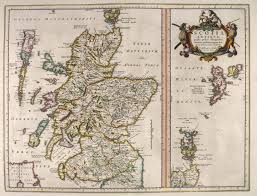

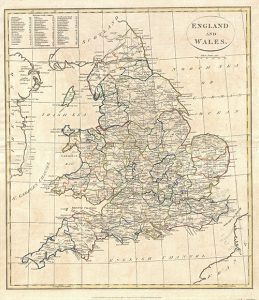

The national mapping agency of Great Britain was created in 1745. It began as a systematic mapping of the highlands by the military to document it more effectively during the Jacobite Rebellion. It’s still in existence today, having morphed into the Ordnance Survey in 1784 when mapping of the rest of the British Isles continued in the wake of the Napoleonic wars.

Here mapping is used both for power, knowledge and for political uses but look at how beautiful this map is, showing details of rivers and roads, terrain, field systems and settlements, (all originally useful for an army hunting out rogue clan members in a strange land). It gives a broad bird’s eye view rather than the tunnel vision of the strip map. And the hand of the map maker (even if this was a very collaborative undertaking) can still be felt in the rendering of the terrain and the lettering of the settlements.

By the early 19th century, teams of men were mapping the entire country, systematically measuring distances using the newly invented trigonometry system and noting place names (if not always correctly). There are a number of instances where places were misnamed and never remedied – we still use them today.

This is Thomas Colby, the longest serving Director General of Ordnance Survey. He’s a determined man who doesn’t mind getting down and dirty with his men. He travels with them, helping to build camps and was renowned for once walking 586 miles in 22 days (that’s approximately 26 miles a day). At the end of each survey, the story goes that he arranged mountain top parties around the newly built trig points with enormous plum puddings (the forerunner of the Christmas pudding) for his men. Personally, I don’t think you should turn down Christmas pudding at any time of the year but I know this is a matter of taste.

What I find interesting in these two examples is how the initial sparks – from documenting road systems to quelling rebellion, securing borders, and perhaps even inciting invasion – can lead to distinctly different forms of mapping. And in each case, something of the maker can be seen in the rendering, regardless of whether new technology is used or not. And in each case too, stories associated with the mapmakers are still remembered.

Obviously our own impetus for mapping has changed, as has technology. But instead of allowing the personality of new cartographers to shine through, our maps are becoming more and more homogenaic and bland. Functional but bland.

I suppose I see map making as an artform and I wonder if audiences of future centuries will ever truly wonder with a sense of joy or curiosity why our contemporary maps have been made, who made them and seek out the stories behind them…

I’ll continue in Part 3 with more esoteric tales of pirates, dungeons, city planning and a penis extension (if I can find some images in the public domain!).