Its been a while since I last wrote. But mainly these past few months have been taken up by more writing. Not for a blog though, but for a book about hand drawn maps. The book deal was signed in late July and I hit the ground running as the deadline was mid October giving me only two and a half months to write 16,000 words and complete over 30 full page illustrations. Its been quite a marathon, to say the least.

Hand drawn maps are very close to my heart so it was a lovely chance to learn more about the history of cartography, to look at historical maps and also discover maps made by contemporary artists and illustrators. The whole project has made me swing manically between curiosity, wonder, awe and envy. And as a fine artist it has made me start to question what my own maps are saying and how I can bring something different to the world through maps.

I would describe my mapping as ‘narrative’ or ‘annotated’ and in this chapter, I covered two of my favourite artists. I looked at the maps of Stephen Walter whose ethos and work process very much inspires my own mapmaking. Heavily researched – almost to the extent a novelist might research – his vast sprawling maps team with words and descriptions, some fact and others opinion based. He is interested in ‘the residue’ left by humans on places. Those layers of personality and grimy history that cover landscapes. Scratch the surface and you can find it if you know what you are looking for. It is all still there and is something I find fascinating.

I love that he maps unusual places alongside the more obvious. One of my favourites is the mapping of subterranean London. Sewage pipes and pagan cemeteries. Secret tunnels and unsolved murder burials. The London Underground with it’s now numerous ‘ghost stations’, hidden from the every-day passenger’s view and, apocryphally, left untouched as shrines to the history of transport system administration.

I looked again at Adam Dant’s maps of Shoreditch. It’s a place he clearly knows well and he charts the landscape’s history and also imagined future history with notes, stories and tiny illustrations. His maps of Tudor Shoreditch and Georgian Shoreditch are swimming with be-ruffed and be-wigged characters and details. Coincidentally, like me, he has also mapped coffee houses in London. His work is very much illustrative and the pictures are as important, if not more so, than the text. Like Stephen Walter, his places don’t just exist in one moment in time but have multiple existences all vying for attention. People and places are people and places whatever the century and things don’t change too much really. And a place can only truly be seen if viewed through its many historical transparencies.

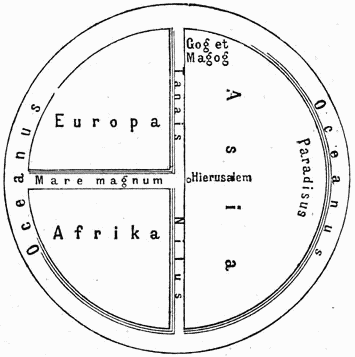

Throughout the book, I wrote about different ways to map. Artist Kate McClean’s sensory maps that document places through smell for example. Or artists who map the landscape of their hands through their personal history of touch. Ancient techniques of mapping were also unfamiliar to me. The Greenlander Inuits who map the coast and fishing grounds by carving the shoreline into knuckle-sized pieces of wood. Small enough, waterproof and lightweight, they are obviously easy to carry in a canoe somewhere.

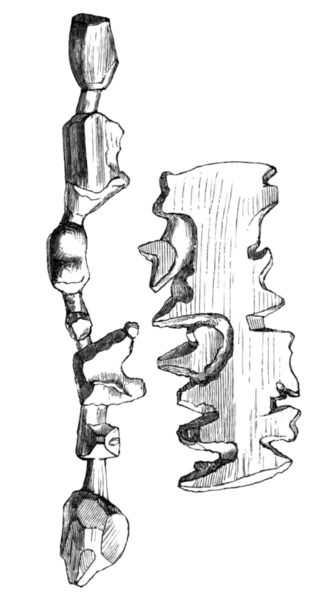

Polynesian seafarers, exploring and settling the Pacific islands, tie sticks together to make grids of the oceans. The wind and waves swells are represented by palm tree fronds and the islands themselves by shells. They mapped with the very basic resources available but gave a clear description of place and how to get there. As maps they work pretty well.

So where does this onlsaught of image and information leave me? I know that I too am interested in the palimpsest of history left on a landscape. And that the concept of ‘place’ is more than cold geography – it’s full of stories and feelings and individuals – and these are the things that, at best, can only be vaguely interpreted from traditional mapping systems and are evicted entirely from modern GPS systems. I want to continue exploring that theme.

Another thought that interests me is to look at more rural environments. I’ve realised through this time of research and writing that so much mapping is centred around the city. I have written before about how the use of traditional maps can protect a landscape by bringing us a greater understanding of our place in it. And I’ve already touched on mapping wilder, less urban places like the Sussex Weald and the North Atlantic. Can mapping be used with a green activist agenda? Or simply to document rural places before they disappear under concrete?

As for what those maps will look like, I don’t know… The maps I created for the book were so diverse in format that they look as if there was a whole multitude of artists involved. It was a brilliant excuse to play and I was working with a very open minded publisher who didn’t seem to mind that they had little of my usual style.

This does leave me in a place where I am questioning how I move forward stylistically with my work though. I guess, it may be a case of further play and seeing where my current style of fine lines and hand lettering can merge with the best parts of the new maps I have created. Perhaps using paint, perhaps something entirely different (although sticks and cowrie shells might be pushing it a bit – I will always love the drawing….).

As ever, after any such adventure, I need to factor in some percolation time. Let the months of maniacal scribbling and lost-in-maps mesmerism bed down. Let my head and eyes rest. I don’t know where my book about hand drawn maps will get me but I’ll go somewhere with it. For sure.

I am in awe of the accomplishment.

Thanks Karen! X