The following is adapted from an article I wrote recently (as yet physically unpublished) about how traditional maps are important in reminding us of our relationship with the environment.

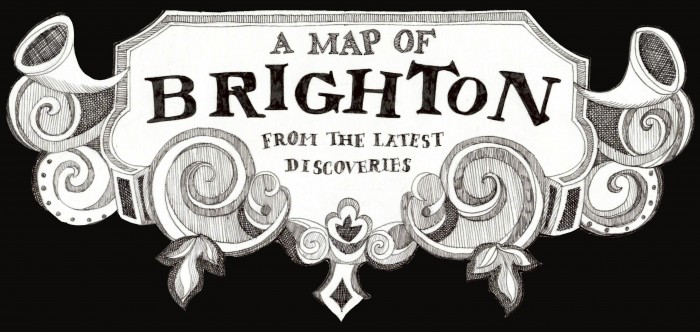

I am an established illustrator and artist – I have been published in over 30 books but in the past few years my fine art practice, emerging through gallery exhibitions (encouraged strongly by Onca Gallery, Brighton), has concentrated on hand drawn artists’ maps.

Onca Gallery is a centre for arts and ecology supported by the Arts Council amongst other partners. They ‘curate and host exhibitions, performances, outreach and events that ask questions, tell stories and initiate conversations about environment and social change.’

Traditional maps fascinate me, even more so now that Google Maps and GPS have become the go-to source for finding directions. Are we are losing the mystery, stories and character of maps found on paper, I wonder? The labyrinthine folds, the arcane symbols, the decodifying of contour lines signal adventures to unexplored destinations. Even well known territory can throw up new discoveries when you open a map. Every river, every holt and coombe narrates a tale of human interaction with it. GPS ignores all of these, denuding our landscapes of such features in favour of fast linear travel.

In order for us to value our environment and make efforts to protect it, perhaps we need to positively accept our place in it. We are of nature, not outside nature. We are part of and have been part of the environment for centuries and our traditional maps show this. By recognising the value of individual human narratives within the environment, I suggest that we might cherish those places just a little bit more.

Understanding environment through story comes very naturally to people. We often describe where we are by relating stories to each other of our personal interaction with a place. For example, a walk around my home city of Brighton can be described by using small personal tales – this corner is where we danced on New Year’s Eve or this café sells the best coffee in town.

Small historic stories exist too if you know where to look. Round the corner from the best coffee in town is the gravestone of Sake Dean Mahomed in the grounds of St Nicholas’, Brighton’s oldest church. He was ‘shampoo surgeon’ to George IV and opened the first Indian restaurant in England. Layers of knowledge and stories about a location from both past and present can exist at the same time.

As an artist, I fill my hand drawn maps with stories and details about each place: historic, contemporary, anecdotal, personal, fictional and real. I map the subjects and places that interest me. The urban is as important as the wilderness. All are part of the environment.

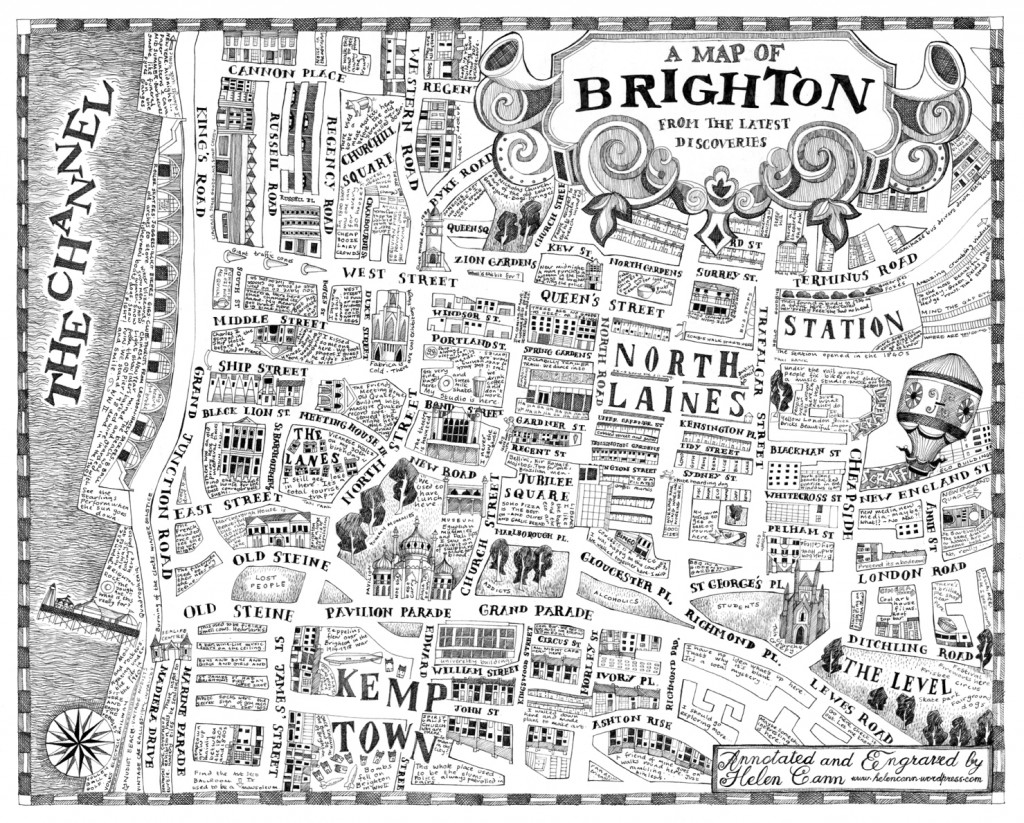

Another project, ‘Echolocation’, commissioned by Onca and in collaboration with Sussex Wildlife Trust, maps the flight path, probably centuries old, of a rare Barbastelle bat. Alongside the contemporary scientific data provided by SWT, the map also describes the local history and folklore of that part of the Weald and some of the 30 different words for mud in the Sussex dialect. The sounds of both man and bat echo in this area and by acknowledging that, perhaps we are more likely to value the landscape (and therefore the Barbastelle habitat) itself.

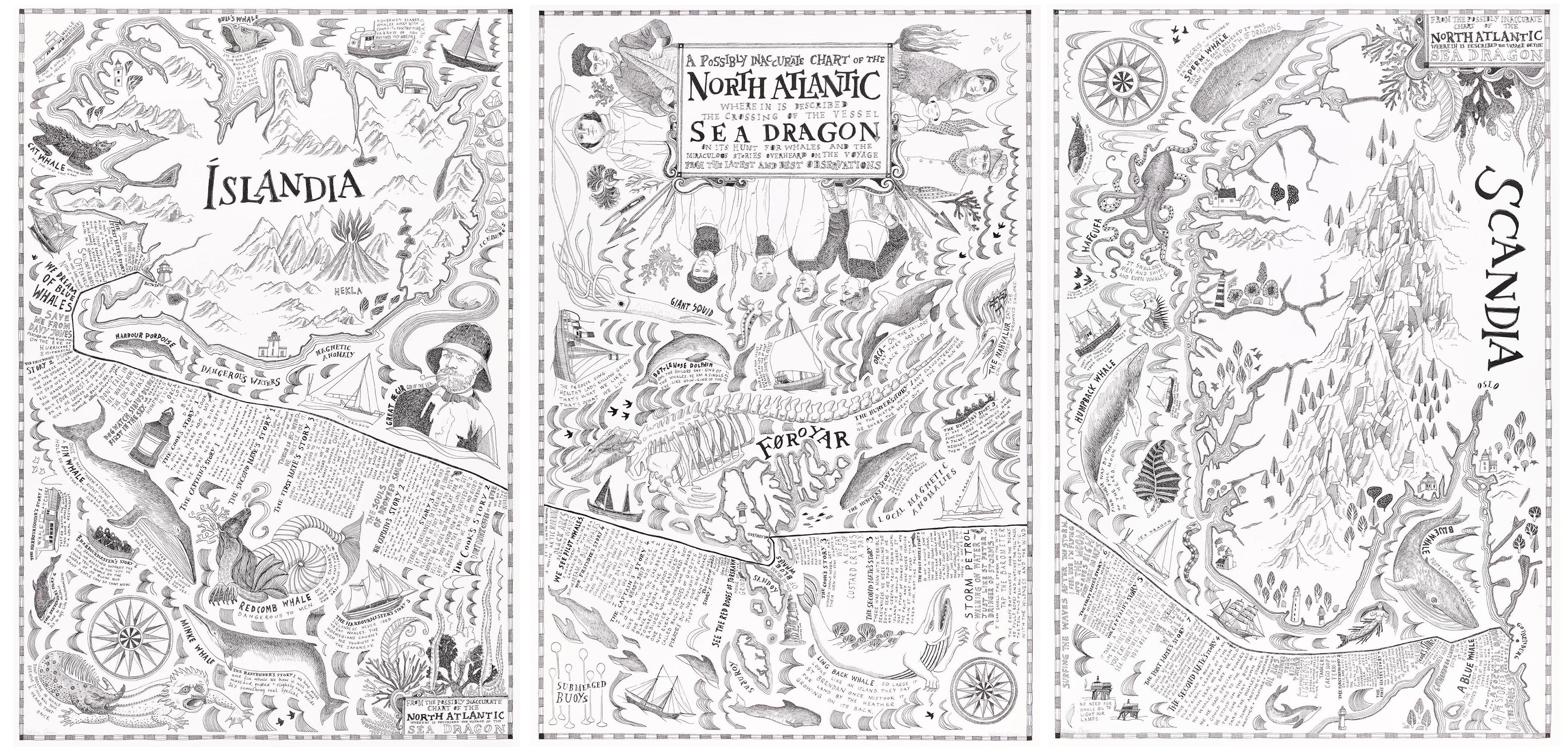

One of my most recent and largest projects was the result of an artists’ residency (again organised by Onca) sailing 1300 miles from Reykjavik in Iceland to Gothenburg in Sweden. We not only helped crew the boat but also mapped whale sightings onto an international marine conservation database. My goal was to see a blue whale but the reality was we saw ominously few whales, of any kind, at all– so few that they became almost as fantastic as the sea monsters of legend.

The piece became a chart of the voyage covered with travellers’ tales, both contemporary and historical, interspersed with fantastic stories of whales and whaling from the past. I collected stories from the crew. I collected stories about whales from Grindadrap hunters in the Faeroe Islands, from tour guides, harbour masters and bartenders…

It became clear that the stories men tell about the oceans had changed very little throughout time. The stories of pirates, ghost ships, mermaids and rum were still being told alongside the stories of fabulous sea monsters, that were often chased, half glimpsed but never fully seen. The cultural value of whales shouted out loud and strong as did the cultural value of the sea. GPS loses all the stories we have of our historical relationship with the waters.

The journey ended at the Gothenburg Natural History Museum alongside the massive presence of the Malm Whale. Ironically, this was the closest I came to seeing a blue whale. It had beached in the 19th century, been preserved and had its jaws articulated allowing tourists to walk inside. At one point it became a cocktail bar but was closed after the discovery of a ‘semi-naked courting couple’ making out inside…

Just another story…

Traditional cartography is becoming a lost art with the ubiquity of soulless GPS and Google Maps. All those stories that truly allow us to understand a place, once illustrated on maps, will be abandoned and perhaps we should be aware of what we are losing. Gone will be those marks we have made on the landscape, the naming of villages, the fighting of battles, the dew ponds and drove roads and echoes of settlements. All these will be lost stories. And by losing them, we will have one less reason to appreciate and protect our environment.

I think it’s important to express that there is more to a place than simple geography and that there are multiple ways to understand, describe and navigate our world other than the digital. Appreciating all that makes an environment and the story of our place in it is fundamental in encouraging a greater love and deeper respect for where we live. Traditional maps tell stories and we should be careful not to forget them.

Nice read. Given me lots to think about. Maps as narrative built by creator/audience interaction + the variants in the past and digital annotation/accretion.

Hi Liam,

I guess maps are, by their nature, always curated and edited by the cartographer-creator within a particular context and for differing purposes. Certainly the stories that the map creators choose to tell depend on these particular variables.

I think my love of traditional maps (that inform my own map making) comes from reading the clues of evidence of past people’s lives in the landscape – for example Old English place names, super straight Roman roads, 19th century chalk pits etc. All previously indicated on maps. These details become a palimpsest of our relationship with an environment.

My feeling is that the current digital annotation of GPS is so simplified that these details are lost and with them, our understanding of our own human history in the landscape.

I arrive at the conclusion, after reading your blog and looking at your drawings, that there are 3 kinds of maps. Google and GPS, traditional maps and your maps.

The first two I can use to get me somewhere. The last one takes me traveling.

Xx

Hi Ramon – but I think traditional maps (like Ordnance Survey maps) can take you travelling too… Our history with a place is marked on those maps through the naming of settlements, non-urban areas like fields and woodlands and marked features like battle sites or windmills for example. All the names are clues to the stories of our relationship with the environment…. You can still use an OS map to get you somewhere, but unlike GPS or Google maps,you are given a much richer understanding of the place you are in.